Published on: March 7th, 2016

Last modified: February 16th, 2024

Heather Richardson meets the founder of Building Schools for Burma, Patrick Gilfeather.

Paddy Gilfeather’s grandparents met in Rangoon. His grandfather moved from Glasgow around 1930 to work for the Burma Oil Company (BOC) as an engineer when the country was part of the British Empire; there he met Paddy’s grandmother, and the pair got married in Rangoon, which is now Yangon. When the war broke out, his grandfather fought in Burma and India, and when the Japanese arrived he was sent to Iraq to pump oil. Meanwhile, his grandmother and her daughters left Burma on foot, walking all the way from Rangoon across the mountains to Bangladesh. She managed to get on a plane to South Africa and finally boarded a boat home to Glasgow.

It was his grandmother’s diary – an “amazing family document”, says Paddy, complete with receipts and photographs – that inspired him to visit Burma (now Myanmar). He was fascinated by the exotic-sounding places. Ten years ago, he set off with the purpose of recreating his grandparents’ photos, including their wedding photo, which was taken in front of the Shewedagan pagoda in Yangon. Paddy’s experiences in Burma led to a serious relationship of his own.

On that first trip, he visited a school in Nyaung-U. “I wanted to see village life, see hospitals, I wanted to see schools,” Paddy says. “I met this one guy in Bagan and he took me in his horse and cart around the temples – it was absolutely fabulous, I loved it.” The next day, the same man – who is called Min Min – hesitantly showed Paddy around his village.

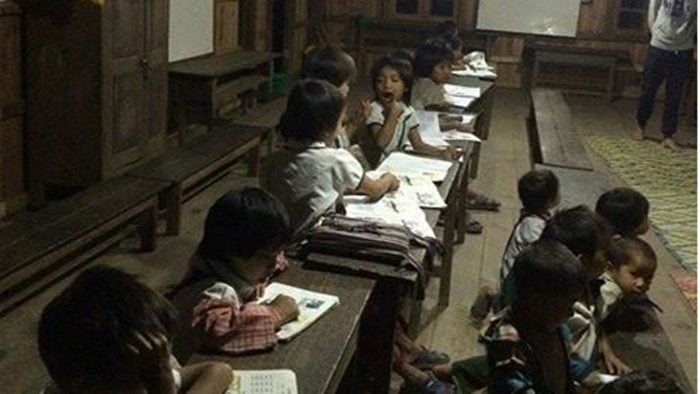

“He took me to this school, which was a monastery on the outskirts of Nyaung-U. They had 80 or 90 children in this school who the monks were teaching. The kids were queuing up to get into school. Some of them literally just had flip-flops and shorts – that’s all they had.” Paddy had bought some pens and books with him, but felt like he could do more.

The next year Paddy came back with $200 to spend on books, pencils, educational posters and blackboards, but he realised that what they really needed was more classrooms.

Paddy went back to the UK and thought ‘let’s do this properly’. He set up Building Schools for Burma and after completing the painfully slow process of registration and fundraising for a country people didn’t really know much about, he finally had enough to expand the monastery school at Nyaung-U with four new classrooms, each big enough for 50 kids. There are now 450 children at the school.

“Children in Burma pay to go to school, they pay for their uniforms, they pay for books. A lot of people simply can’t afford to pay that. So, this monastery provides free education. They don’t have to wear uniforms. They don’t have to worry about buying anything. When we go out there and we give a child who has absolutely nothing a book, a pencil, a rubber and a sharpener, you see their eyes light up – that’s theirs to keep.”

Kids can now stay at the school until they’re 14 or 15, rather than 12. “They don’t have to stay, but they are welcome to,” Paddy says.

When the school was completed, Paddy was delighted. “People said, ‘you’ve done it’,” he remembers. But Paddy wasn’t ready to stop. His goal was to build a school in each of Myanmar’s seven states.

Ten years after that first visit, Burma has transformed, emerging from the shadows as one of the new ‘must-visit’ destinations in Asia. Bagan, Inle Lake and Yangon have all become popular places to visit, and the suspicion of the locals towards tourists – largely a result of government propaganda – has melted away.

Despite tourism bolstering the economy, there is still a lot of poverty. About eight years ago, there was a massive storm, Cyclone Nargis, which killed an estimated 140,000 people, although the UN have estimated the death toll to be 200,000. The tidal wave was three storeys high and demolished a huge area of the southwestern delta region. It was the worst flooding in 60 years and the tsunami and resulting landslides destroyed homes, businesses and schools.

In partnership with a Burmese lady named May from Chiswick in west London and her English husband John, Paddy was able to build his second school in the delta region, which he describes as a “very, very poor area, still struggling to recover from that storm eight years ago.”

Paddy’s third school is in the mountainous Chin State, one of the poorest states in Myanmar and located by the Bangladesh border. In the small village in which the school is based, the women have tattooed necks and faces and are animists, which means they believe in animal spirits. There are 80 different tribal people in Chin State, each with their different identities and tattoo patterns.

“Sometimes you feel as if [certain tribal people] are wheeled out for tourists,” Paddy comments. “This was actually the real deal – they don’t see any tourists, because there’s no reason for people to go.” Chin State is remote and difficult to access. From Bagan it takes a couple of days in a 4×4 to cross the mountains and reach the village.

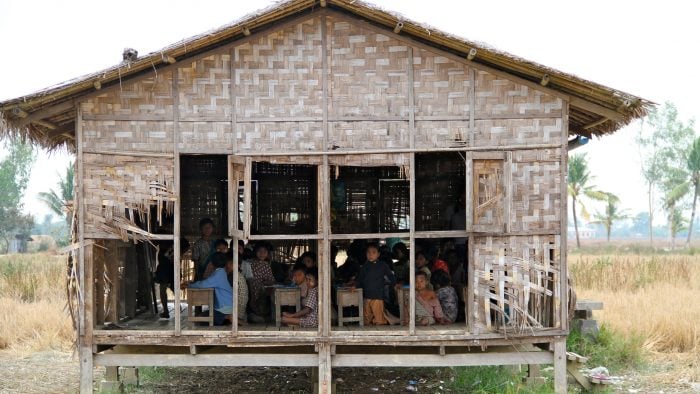

The region was also badly affected by the floods, so Paddy put aside his target to build one school in each state and started the fourth in Chin State. This one will cost around $12,500, including a concrete foundation, teak wood, a zinc-tin roof, wooden floors and tables and chairs. They will also be constructing two toilets, a water tank and solar panels from India, which is particularly important in a state where there is no running water or electricity.

“What it means is that the children, their parents and grandparents, who might not have had an education before, are invited to the school to learn to read and write – it’s not just the children,” Paddy explains. “I’ve said it should be a place where community events can happen, not just schooling. It should be a safe place that people can go to. I’m very much a firm believer in community.”

Sustainability is at the heart of the projects. “All I want to do is give them a helping hand and then they can help themselves,” Paddy says. The schools also provide jobs for local people. “Yes, we provide the money,” said Paddy. “But we use local builders, local architects, local merchants, local labourers – that way, the money we’re spending is stimulating the local economy.”

There’s an advantage to Building Schools for Burma remaining a small operation. “We’re a micro-charity. It’s me and a few valuable people who help me,” Paddy explains. “We don’t have any costs. This is a crucial point, which I think differentiates us from any other charity. Every penny we’re given goes to the next project. So, when I go out to Burma, I pay for my own flights, I pay for my own hotels, I pay for everything myself. I give up my time because I love it and I want to do it. All the other people involved – accountants, administrators, web designers – give up their own time and do it for free.”

Another advantage is that they can access areas of Burma off limits to bigger institutions. These remote places are often the areas that need help the most.

So far, Paddy has raised enough money to build four schools in total, with a fifth on the way to completion. He’s hopeful for the future. He thinks they can build two schools a year and imagines the fifth school will be built by the end of March 2016, with the sixth funded by the profits from a specially created handbag by design house Land of Ed.

Paddy doesn’t see the project finishing any time soon. “As long as I’ve got the hunger, I will keep on doing it. There’s no reason to stop. It’s my love for the Burmese people and the country as a whole. For me, it was very difficult not to do something.”

Building Schools for Burma is one of two charities Jacada Travel supports in Asia. For every trip to Asia we plan, we donate a set amount to the project.

All images by Patrick Gilfeather.